So much of the American collective conscious relies on the possibility of redemption. In fact, redemption is one of the great themes of American literature. Think about the classic, and often grizzly, works by Flannery O’ Connor and William Faulkner that so elegantly portray characters seeking something different from their chaotic pasts—something they can grasp that can free them from their guilt of sins.

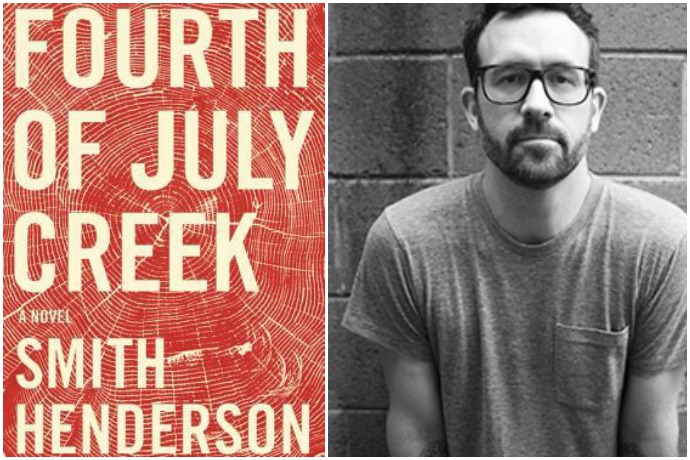

Smith Henderson’s debut novel, Fourth of July Creek, is the latest offering in redemptive Americana, and it’s downright masterful. Henderson’s work tackles the same subjects that populate O’Connor and Faulkner’s best writing—religion, grace, violence, and, of course, redemption.

Fourth of July Creek follows the life of a Montana social worker named Pete Snow. Early on, we find out that Pete is a sinner, but he’s an okay guy. You know, he’s normal. He’s made mistakes, but he’s working to patch up his life. As a social worker, he gets to go into homes and protect the child inhabitants. He finds joy in his work because he gives children their salvation. What Pete struggles with, though, is maintaining his personal life.

His relationship with his family is essentially non-existent. Henderson writes of the moment that Pete’s daughter knows the relationship with her father is lost: “When she realized that he chose the job, that he wanted to be there for the other families. That he didn’t want to be there for the one he had.” With such a proclamation, Fourth of July Creek makes it rather obvious that Pete spends little time with his own daughter, who has, herself, fled to a life of drugs and sex. He wants to save her—like he does his other “kids,” but life isn’t that easy. We can’t go from complete separation to acceptance within a span of days or weeks—probably even years. Too, such redemption would be an easy copout in a novel that is raw and brutal.

Henderson turns his focus to Pete’s hope for becoming a better man—not necessarily a better father. His decision to do so works beautifully. Pete faces worldly temptations, and he occasionally succumbs to them. However, when evil stares at him, he faces it with boldness.

Pete shows his redemptive behavior in two separate quests. The first involves Pete’s interactions with a teenager named Cecil. Cecil is a boy who can’t get along with his mother. He is violent, and she, too, responds in angry mannerisms. Pete comes to the rescue of Cecil and finds a home where Cecil can live peacefully. Well, things don’t go so well. Pete struggles to get Cecil to understand that second chances are tough to earn and shouldn’t be wasted by making stupid decisions. Cecil finally breaks down, just as he is being pushed to what he imagines as his personal limit. Cecil asks Pete, “Can I stay with you?”

Cecil’s question is direct and it’s a sincere request. What makes the narrative so powerful is that we know how Pete wants to respond. We know that he wants to cave in and care for the troubled boy. We know he wants his chance to redeem himself as a father. But, Pete also is the same man that he was when he failed his daughter. He knows this, and because of his own awareness, he essentially redeems himself. He makes a responsible decision, albeit a difficult one.

Pete’s other conflict is with how to handle young Benjamin Pearl. Benjamin, like Cecil, is a boy who comes from a very rough background. His father, Jeremiah, is a religious fanatic, proclaiming sin to fill just about every object in the boy’s vicinity—including childish cartoons. Benjamin’s mother, brothers, and sisters are all dead, presumably (at least for most of the novel) by actions of Jeremiah.

When Pete first meets Benjamin, the boy is malnourished and desperately in need of new clothing. Pete tries to help the boy by giving him necessary goods, but Jeremiah refuses the charity and threatens to kill Pete if he tries to get close to his family again.

Again, Pete has to decide what to do, and, for the second time in Fourth of July Creek, he does the right thing. He puts his life on the line by visiting the Pearls again. Pete’s job is to make sure Benjamin is okay, and he does so.

Eventually, Pete is able to speak with Jeremiah, and the two come to an understanding. However, their truce comes just when outside problems start appearing. Without revealing too much of the plot, I can say that the ending is incredibly explosive, spewing with violence and rage.

Pete has a moment with Benjamin where he thinks he might can save the boy. Then, he remembers who he is. He’s a man who is in love with his job. He’s in violent situations every day. He is never at home. He doesn’t take care of himself. Just before he says the wrong thing to Benjamin, Pete says, “Never mind. The other thing won’t work.”

By refusing to take on the responsibility of another life—not once, but twice, Pete Snow redeems his past mistakes. He shows that he is a guy who understands what he can and cannot do. In other words, he becomes a man.

Henderson is in command from the first sentence until the very last word. It’s hard to believe thatFourth of July Creek is a debut. The dialogue is rich, populated and fulfilled with a variety of characters. The pacing is also noteworthy. Just looking at the heft of the book, you might imagine that you’ll spend a month getting through it. Trust me when I say that you won’t. These pages fly. You’ll be racing to get to the next chapter. It’s a roaring, untamed read.

Atmospheric and written in a haunting prose that is tightly focused and spectacular in execution, Smith Henderson’s Fourth of July Creek is an American masterpiece.

THE BREAKDOWN

10 - CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

9 - STYLE

10 - LITERARY MERIT

9.7 TOTAL SCORE