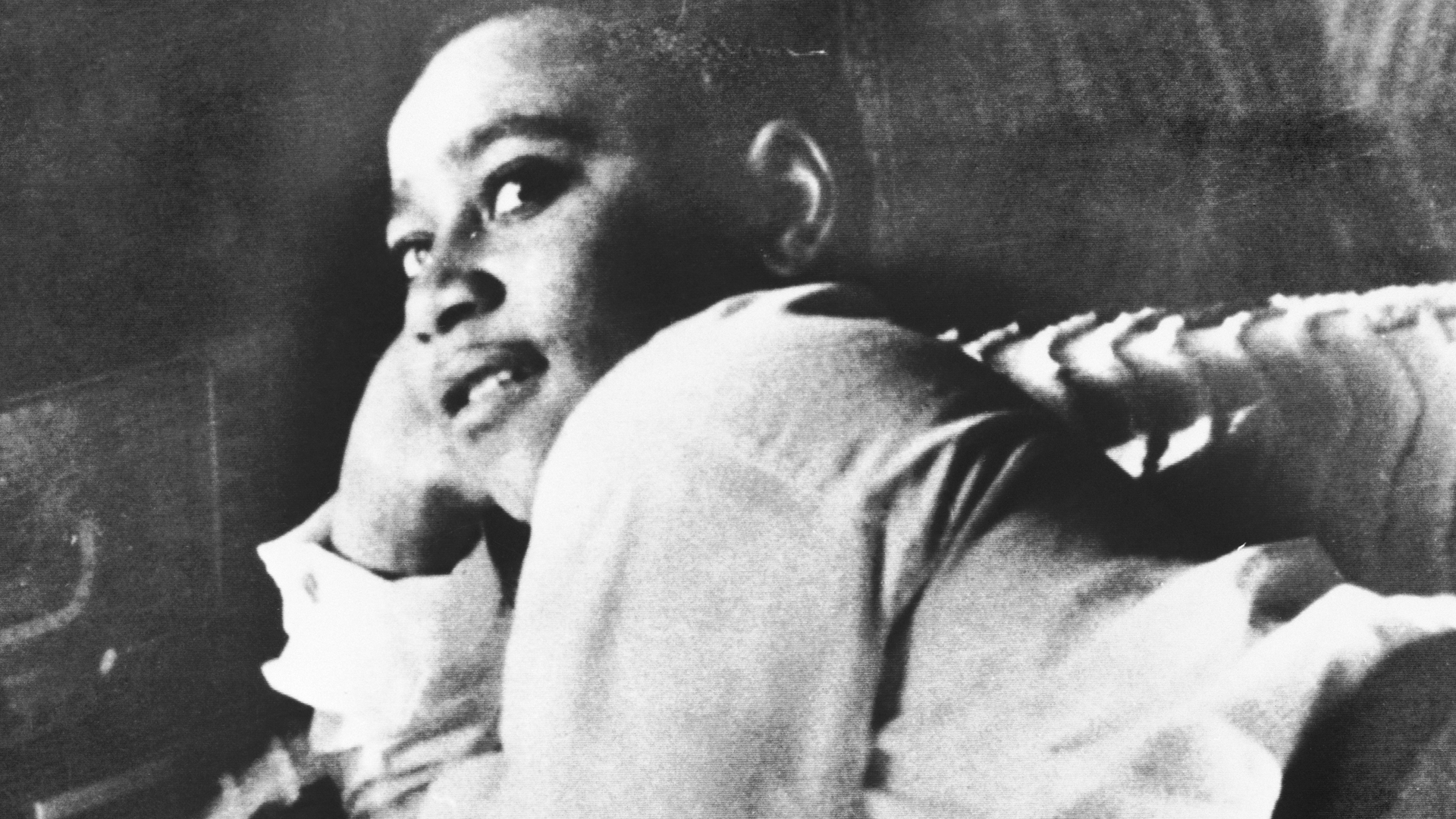

In 1955, Emmett Till was murdered. He looked wrong. He’d looked at someone who looked wrong. However you’d like to put it. He did nothing.

Then we caught the killers. Wasn’t hard, because there was nothing surreptitious about their murdering. Their motives were loudly proclaimed. We didn’t have a cellphone recording of Till’s final moments, but we had most everything but.

The killers were found not guilty. Free to walk.

John Edgar Wideman was fourteen – the same age as Emmett Till – in 1955. He was growing up with brown-hued skin in Pennsylvania. Naturally, the news rocked him. It hurt to learn that his life didn’t matter. Like kids these days watching Trayvon Martin’s killer walk: a clear message, your life here is tenuous.

In Writing to Save a Life, Wideman explores the way Till’s murder affected his own life, both when he heard the news in 1955 and, later, when he set about researching why the killers were not punished.

In Wideman’s words:

Federal officials pressured the state of Mississippi to convict Milam and Bryant of some crime. Since abundant sworn testimony recorded in the Sumner trial had established the fact that Milam and Bryant had forcibly abducted Emmett Till, the new charge would be kidnapping. Justice Department lawyers were confident both men would be found guilty.

Except, two weeks before a Mississippi grand jury was scheduled to convene and decide whether or not Milam and Bryant should be tried for kidnapping, Emmett Till’s father, Louis Till, was conjured like an evil black rabbit from an evil white hat. Information from Louis Till’s confidential army service file was leaked to the press: Emmett Till’s father, Mamie Till’s husband, Louis Till, was not the brave soldier portrayed in Northern newspapers during the Sumner trial who had sacrificed his life in defense of his country. Private Louis Till’s file revealed he had been hanged July 2, 1945, by the U.S. army for committing rape and murder in Italy.

With this fact about Emmett Till’s father in hand, the Mississippi grand jury declined to indict Milam and Bryant for kidnapping. Mrs. Mamie Till, her lawyers, advisers and supporters watched in dismay as news of her husband’s execution erased the possibility that killers of her fourteen-year-old son Emmett would be punished for any crime, whatsoever.

Violence begets violence. One crime leads to another. Although the story is not – as the white people of Mississippi presumed – that a rapist father sired a rapist son, a boy who perhaps really did ogle that white woman, or whisper crude nothings in her ear, or grab her.

It is true that when the white people of Mississippi learned that Louis Till – Emmett Till’s father – had been hung for rape, they lost all interest in punishing Emmett’s murderers. Their reasoning was similar to the U.S. Supreme Court’s logic as the crusties on the bench have issued ruling after ruling undermining the Fourth Amendment.

After all, our courts rarely hear a case relevant to the Fourth Amendment unless the defendant is clearly guilty. We have constructed a world in which police officers are rarely punished for subjecting innocent people to excessive force or aggressive searches. If you are stopped by an officer and your car is illegally ransacked… or if you are illegally frisked, the officer groping your crotch and buttocks… or if you are a thirteen-year-old girl illegally ordered to strip to ensure you’re not hiding Advils in your bra or underpants, after a classmate claimed you might have some … there is no redress. The authorities will not be fired. They will be subject to no punitive fines. You will receive no restitution.

Our courts have stated that “government officials performing discretionary functions generally are shielded from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.” Which doesn’t sound so bad until you realize that the courts think a reasonable person might not be aware that strip searching children in front of their peers isn’t cool. The courts think a reasonable person might not realize that it requires a “no-knock” warrant before a SWAT team busts into a small-town mayor’s family home and murders his pets. Freedom from egregious, unwarranted harassment is not a “clearly established” right that a “reasonable person” would know about, so cops are shielded from personal liability.

Instead, the only punishment our courts are willing to impose on police officers is the loss of their precious evidence. Which means that, if cops screw up, we all suffer. Instead of the officer in question paying a fine, we must allow a criminal to walk free. This is the “exclusionary rule,” courtesy of 1914’s Mapp v. Ohio: evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment can’t be used to prosecute somebody.

But the courts – fearing that somebody who commits one crime will surely commit another – are loathe to levy that penalty. It’s clear that what officers do is sometimes wrong, but when an officer’s illegal behavior catches someone else’s illegal behavior, they imagine that two wrongs make a right and throw the criminal in jail. Given that only criminals have any chance of redress, the courts only hear cases in which the cop’s illegal behavior worked; they never learn about the thousands of innocent citizens harmed to catch that one criminal. And, to say on the sunny side of the exclusionary rule, each time the courts must decide that the Fourth Amendment was not actually violated.

Which leads to situations like the Supreme Court justices – perhaps bamboozled by popular press articles about quantum mechanics – arguing that information can travel backward through time. That if an officer learns that someone is out on warrant midway through an illegal search, the search retroactively becomes legal.

This is blatantly foolish. Those justices who voted with the majority on Utah v. Strieff should feel ashamed. Justice Sotomayer wrote a fine dissent, but any fourth greater could compose a perfectly lucid dissent for this case. Despite what the pentad of hate machines on the majority thought, time travel only works in science fiction.

But they were loathe to let a “bad man” walk free.

Similarly, the grand jury in Mississippi knew that, yes, kidnapping and murder are bad… but if Emmett Till was also bad… don’t two wrongs make a right? If Louise Till was a rapist, they figured, isn’t it likely that his son was a rotter too? Violence begets violence.

But what if… what if violence against Louis Till begat the violence against his son? What if Louis Till was framed for rape – murdered by the United States to allow criminals to walk free – and the murder of Louis Till allowed Emmett Till’s killers to walk as well?

Wideman combs the once-confidential military file of Louis Till (unsealed in 1955 to be leaked to the press), searching for truth. He does not find it. He cannot. In his (frustrated) words:

Will a moment finally emerge in which a collection of lies offers access to truth. More truth, anyway, than a single individual – liar or honest person – is capable of reconstructing. Which lies. Whose lies. The file writes fiction. To mimic reality, the Till file writes fiction.

Wideman learns that the victims’ testimony varied over time. He learns that several unrelated crimes – occurring in different locations – were linked together and pegged to the same group of men so that as many cases as possible could be “solved” at once. He learns that local commanders were pressured by the U.S. government to wrap up all cases as quickly as possible. He learns that African-Americans were blamed for an outsize majority of infractions.

In the case of the rape, the victims said the room was too dark to see. They couldn’t see the color of the perpetrators’ clothes. They said one of the assailants lit a match. They said the perpetrators were black men.

One witness said he’d spent time in the United States and could recognize different accents well. In his first statement, he reported that the speakers were definitely not African-American men. It was too dark to see, but he knew they were white from the timbre of their voices. In later statements, he’d reconsidered: the men who broke in to rape the women definitely were African-Americans. Originally, four men had broken in. By his second statement, there were only three.

And, yes, it was these three. We couldn’t see anything.

Louis Till was found guilty, beyond a reasonable doubt. He was murdered by the government of the United States. And his guilt allowed the men who murdered his son to walk free.

Till’s crime is a crime of being, I decide after spending hours and hours one afternoon, poring through the file, an afternoon not unlike numerous others, asking myself how and why the law shifted gears in its treatment of colored soldiers during World War II. Asking why colored men continue to receive summary or no justice, a grossly disproportionate share of life sentences and death sentences today. Whether or not Till breaks the law, his existence is viewed by law as a problem. Louis Till is an evil seed that sooner or later will burst and scatter more evil seeds. Till requires a preemptive strike.

As Wideman researches this history, he also reconsiders events from his own life. During the summer of 1955, Wideman, the same age as Emmett Till, had sex for the first time. It was an unexpected boon from the universe, an event not to be repeated for many years. A girl named Latreesha – more experienced than Wideman, and sent away from New York City for the summer because her parents feared she was growing up too fast – was boarding at Wideman’s grandmother’s house. Soon after she arrived, she and Wideman kissed, took off their clothes, and, briefly, fumblingly, had sex.

Then she dumped him. She started hanging with boys old enough to drive. How was 14-year-old Wideman supposed to compete with any 16-year-old with a car?

For that one day, though, Wideman felt he was in love:

You snuggled down with me again after you’d used the bathroom, shut up my dumb questions, my worries with your tongue searching for mine inside my mouth. All those dumb questions, and here’s another for you. Or a couple, I guess. On this first visit after so many years, is it strange for me to ask, Latreesha, strange for me to think you might know the answer. Did Emmett Till ever get a chance to make love.

That final sentence hurts me. That question – although it’s presented flatly, with a period. Unanswered, unanswerable, just like all the other question-mark-less questions in Wideman’s book.

That final sentence got me thinking about a kid I knew from jail. He had been incarcerated since he was sixteen, already on his third year in the jail when I first met him, still awaiting trial. Innocent until proven guilty? That’s only true for people wealthy enough to pay bail. For poor people, punishment starts as soon as they’re accused, innocent or not. And this dude’s family was the kind of poor where kids go hungry in summertime because they lose the schoolday free lunch.

One day, broke and hungry, he attempted to rob a convenience store. He stomped in with a BB gun. That made it “armed robbery.” They were going to try him as an adult and started the plea bargaining with him looking at twenty years.

And he’s dead now. He was nineteen when he died. He collapsed about an hour after I left the jail for the second creative writing class I’d taught there. He’d gone without medication for his very treatable heart condition ever since he turned eighteen; as a legal adult (pay no heed to the fact that, for sentencing, they’d been considering him an adult since sixteen), his broke ass would’ve had to pay for the pills. He needed beta blockers. Generics cost about five dollars a month, but between that and the fee to have the jail nurse bring one to him every day in a little paper cup, his family couldn’t pay.

He was very sweet. Beloved by his cell mates. And he always put a positive spin on their circumstances. For instance, the food: “When I get out, my mom’s not gonna bring biscuits and gravy right to my room. When I get out, we’re not even gonna have biscuits and gravy.” But at the first writing class I taught in there, he was posturing, trying to sound tough.

“Whatcha like to read?” I asked him.

“Hood books.”

“Oh yeah? What’s best about ‘em?”

“The sex scenes.”

170 hours later, he was dead.

I cried when I heard. And, yes, I’ll admit: one of the first things that went through my mind was that this kid, locked up at sixteen, totally broke his whole life, was probably a virgin reading those raunchy sex scenes.

We killed Emmett Till. Our ancestors constructed this world – they’re the ones who hoisted the ropes, who heated the irons, who pulled the trigger – but we still reap rewards from their decisions. All of us wealthy enough to have a safe place to sleep and enough to eat benefit from their past violence. We’ve inherited their riches, their progress and culture and technology, which means we must also inherit the blame. It’s on us, that murdered child. We, as a people, have never made recompense. And think how little of life he had a chance to experience.

We’re still doing it. We’re still stealing the lives of children.

He said he liked reading for the sex scenes, and I just laughed.

Frank Brown Cloud teaches creative writing at the Monroe County Jail and serves as director of the Indiana Prisoners’ Writing Workshop, an offshoot of the Midwest Pages to Prisoners Project. His writing has appeared in Stirring, The Coachella Review, and The Offing, among others. He received his B.A. from Northwestern and his Ph.D. from Stanford.